Underground symbiosis counters drought

When the going gets tough, we all need a helping hand, and trees are no different. Researchers in the Plant Sciences Department at the Weizmann Institute of Science have discovered that in drought conditions, cypresses get help from soil-beneficial bacteria in a kind of cooperation that enables them to survive and even flourish. “Our study might have supplied the best evidence so far that trees and bacteria can really coexist symbiotically,” says Dr. Tamir Klein, head of the research team. “This has huge ecological significance.”

In many places around the world, the summer of 2022 was one of the driest seasons on record. Parts of China, Europe, the Middle East, the Horn of Africa and North America endured severe droughts, and such extreme weather conditions are expected to increase as a result of climate change. According to Klein, the increasing prevalence of droughts creates an urgent need to understand the underground mechanisms that keep trees alive in extreme weather, in order to mitigate the rising mortality of trees in Israel and beyond.

“If we lose forests, we will lose everything because the trees produce our oxygen, absorb carbon dioxide, clean the air and regulate the temperature,” he explains. “So we must support our forests. And if bacteria can support trees and we can understand how they do it, that’s an excellent starting point.”

Klein’s journey to reveal the cooperation between trees and other forest organisms began years ago. In his previous studies, he investigated how trees share resources with other trees to stay healthy, and how they maintain symbiotic relationships with fungi.

The latest study, led by Dr. Yaara Oppenheimer-Shaanan, who is a microbiologist in Klein’s lab, focused on the interactions between cypress trees and beneficial bacteria present in forest soil. For one month the researchers grew cypress saplings in custom-made boxes filled with forest soil, which were placed in a greenhouse at the Weizmann Institute of Science.

The cypresses were divided into two groups: one was regularly watered, and the other was deprived of water. In each group, half of the cypresses were exposed to soil bacteria that had been collected from the Harel Forest, where these cypresses grow.

The research team examined the interactions between the trees’ roots and the bacteria using several methods, including measuring physiological reactions of the trees to dryness, performing bacterial counts, imaging the bacterial colonies in the root zones using fluorescent markers, analyzing the compounds emitted by the seedlings through their roots and assessing the mineral composition of the cypress foliage.

Through this multidisciplinary approach, which combines microbiology, plant physiology and organic chemistry, the researchers identified the surprising cooperation happening underground between trees and soil bacteria: The bacteria help the trees cope with the shortage of water and in return, benefit from the secretions from tree roots.

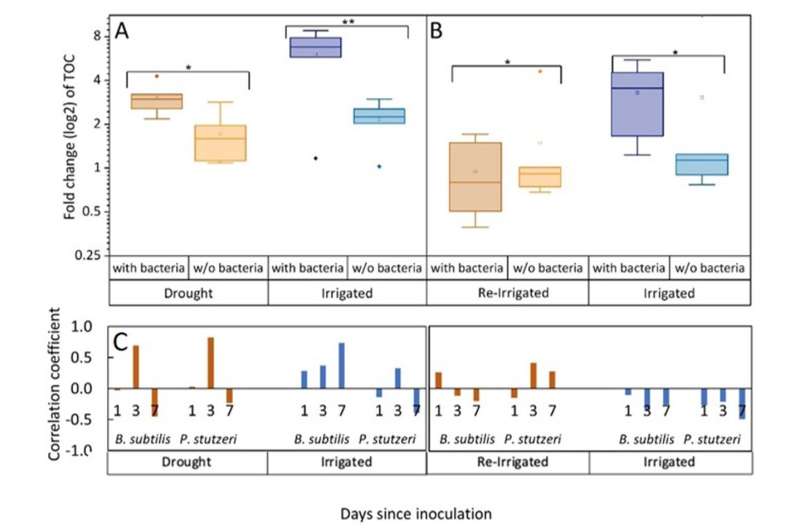

For example, the rate of secretions from the roots more than doubled in trees that were exposed to bacteria, compared to trees that were not, in both the irrigated cypress group and the group growing in droughty conditions. In addition, the scientists identified about 100 compounds in the secretions, including phenolic and organic acids, and the concentration of nearly half of these compounds differed significantly between the irrigated trees and those that suffered from a lack of water.

“When we added nine of the compounds to the bacteria, as sources of carbon and nitrogen, eight of them encouraged bacterial growth,” Oppenheimer-Shaanan says. “This is evidence that the secretions are a source of food for the bacteria.”

Overall, the study’s results suggest that the health of trees improved as a result of interactions with the bacteria. Moreover, during a drought, the cooperation between trees and bacteria offset the negative impact of the lack of water. The availability of phosphorus in the soil was maintained only for cypresses that were exposed to the bacteria, and this availability made up for the decrease in the levels of phosphorus and iron measured in the foliage of cypresses grown under drought conditions.

A complete forest dictionary

Klein hopes that these research findings will advance our knowledge of forest ecology and the understanding that trees engage in much more extensive cooperation than was previously believed. On the applied level, the findings may have important implications for improving soil health and learning how to support plants that are under stress owing to a lack of resources. For example, recruiting specific bacteria could help to improve tree and forest health and build greater ecological resilience and stability.

“The next step is to determine the exact contribution of each bacterium or each group of bacteria, and which bacteria benefit which trees,” says Oppenheimer-Shaanan.

“This is only the beginning,” says Klein. “The more we learn about these interactions, the more we will be able to formulate a comprehensive and accurate dictionary, and this should allow us to arrive at desired results, or prevent unwanted ones, in taking care of our forests.”

The work is published in the journal eLife.

More information:

Yaara Oppenheimer-Shaanan et al, A dynamic rhizosphere interplay between tree roots and soil bacteria under drought stress, eLife (2022). DOI: 10.7554/eLife.79679

Citation:

Underground symbiosis counters drought (2023, July 13)

retrieved 13 July 2023

from https://phys.org/news/2023-07-underground-symbiosis-counters-drought.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

For all the latest Science News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.