The £200bn Covid savings war chest that could prevent a UK recession

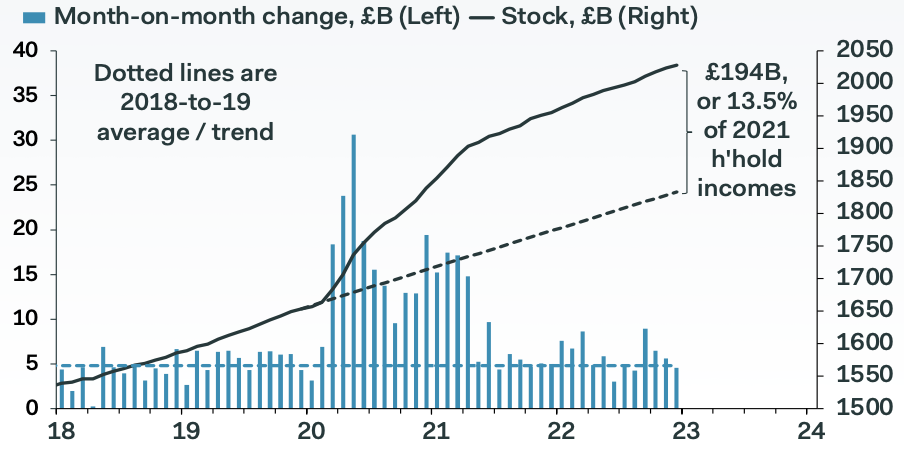

There’s a war chest of nearly £200bn – which started to be built up during the pandemic and has grown ever since – that could save the UK from recession.

This may come as a surprise when all we hear from Westminster is how skint we are, but the stash of cash isn’t made up of tax revenue – it’s your savings.

During lockdowns, when spending opportunities were cut off, households set aside tens of billions of pounds.

The total stock of savings above the pre-pandemic trend is now equal to 13.5 per cent of household incomes. A huge kitty, bigger than anything Jeremy Hunt could inject into the economy at the 15 March budget.

Brits holding onto their so-called “excess” Covid savings makes sense.

The risk of being sacked has risen as businesses are squeezed by rising costs and weaker spending. That dynamic has strengthened incentives to trim down staffing levels to stay afloat.

Higher energy prices, wages and supply chain costs have made producing some products less financially viable, so firms will likely rein in production.

The Bank of England’s 10 successive interest rate rises to a 15 year high of four per cent has tightened the screws on company balance sheets.

Households recognise this. Many people may not understand why they are worse off when their pay does not rise in line with inflation, but they know when something’s up in the economy.

That is illustrated by GfK’s consumer confidence survey, which has been running since the 1970s, hovering at record lows for multiple months.

Savings have swelled since Covid-19 hit Britain

As a result, the allure of spending all that cash squirrelled away over the pandemic has watered down. What if you are laid off? How would you pay your bills? These are questions families are asking up and down the country.

Precautionary saving is something that typically happens when an economy is in the early stages of a recession. On an individual basis, it makes sense to stop spending as much and step up saving. But on an economy wide basis, it’s stupid because it actually sharpens an economic slowdown.

It’s your typical prisoner’s dilemma.

It’s not all about greater caution though.

The flip side of Bank governor Andrew Bailey and the rest of the monetary policy committee aggressively tightening financial conditions is that savers have finally been released from years of getting nearly no interest whatsoever on their rainy day funds.

The best easy access saving account on the market is now from Yorkshire Building Society, offering 3.35 per cent, according to data provider Moneyfacts. This time last year, it was 0.71 per cent from Investec.

Some people, in response to that increase, will have stepped up the amount of cash they set aside each month to capitalise on better returns.

Accounts are also offering rates above the effective rate on all mortgages, “so many borrowers are better off saving now, rather than immediately reducing their mortgage,” Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said in a note last month.

There’s also a surprise effect going on. People, especially younger people, have never had an opportunity to build up a substantial amount of financial wealth due to anaemic wage growth since the financial crisis.

Covid-19, specifically lockdowns, gifted them that opportunity. Spending channels were blocked, meaning, unless you wasted your money on hot tubs, more cash could be set aside each month.

Interest rates have risen sharply

That build up has now made getting on the housing ladder a more realistic end game for many people in the UK. Suddenly spending money down at the pub doesn’t seem so attractive.

But if those savings are left untouched, there’s a real risk the UK will suffer a deeper recession that has been forewarned.

“Demand could weaken by more than expected if some people become more worried about their job security and build up their savings to a greater extent,” the Bank said in its monetary policy report earlier this month.

Lots of economists have assumed the cost of living crisis will force consumers to raid their piggy banks.

The £4.6bn set aside in December was only slightly below the pre-Covid average monthly rise of £4.8bn, suggesting the great savings unwind isn’t gathering momentum.

A big chunk of these pandemic savings are also likely to have been accumulated by the rich as they tend to spend more on discretionary things. This group also is more likely to save each additional pound they earn. Inflation has eroded the value of people’s wealth as well.

Relying on the Great British consumer to power GDP out of slumps is a trope of the economics profession, but one that has consistently pulled through.

Britons, your country needs you(r savings).

WHAT I’M READING

The Institute for Fiscal Studies unearthed some stats on the scale of the bank of mum and dad’s balance sheet.

Some £17bn is gifted or loaned to children each year, most of which is used to buy a house.

“Half of the value of gifts received is reported as used for property purchase or improvement. Those using transfers for this purpose received over £20,000, on average,” the think tank said.

YOU MIGHT HAVE MISSED

Londoners are the most likely in Britain to be working flexibly, according to the ONS. One in four of the capital’s workers do a mixture of home working and coming into the office. The TWATS are here to stay it seems.

For all the latest Lifestyle News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.