Study finds global media reported pandemic xenophobia, but also emphasized global efforts to fight it

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Chinese and Asian communities have faced violence, harassment and discrimination on top of the threat of the virus itself. China was blamed for the virus with terms such as “Wuhan virus” and “kung flu” used by some in power and repeated in the media. A University of Kansas study has found that media around the world reported such terms but also emphasized global efforts were necessary to fight the pandemic and resulting harassment.

KU researchers analyzed 451 news articles from The New York Times, The Guardian and China Daily, chosen for their large readership and for their different international perspectives in COVID-19 coverage during 2020, the first year of the pandemic. The findings show media is very influential in how the public thinks about issues and that care should be taken in cases of naming diseases or threats after regions or people or ethnicities.

“We were interested to examine keywords such as ‘China virus,’ how media represented them and how media constructed these different terms in talking about COVID-19, racism and xenophobia against Chinese and Asian communities in the West,” said Muhammad Ittefaq, doctoral candidate in Journalism & Mass Communications at KU and lead author of the study. “There has been more than a 150 percent increase in cases of assault, either verbal or physical attacks on Chinese or Asian people on the streets, in stores and everywhere. That piqued our interest to understand how media were using these terms in relation to the racism and xenophobia and how different newspapers are overall constructing the pandemic.”

The study, published in the journal Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, was co-written by Mauryne Abwao, doctoral candidate; Annalise Baines, doctoral student; Genelle Belmas, associate professor of journalism & mass communications; Shafiq Ahmad Kamboh, doctoral candidate; and Ever Josue Figueroa, assistant professor of Journalism & Mass Communications at KU and Bremen University, Germany.

The analyzed news coverage fell into four themes:

- Portrayal of the virus as a threat

- Racialization of COVID-19 as a multifaceted threat

- Calls for collectivization to curb racialization of the virus

- Speculative solutions to end discrimination against Asians.

Coverage in The New York Times and The Guardian was found to feature the first two themes more prominently, while China Daily more commonly featured themes of collectivizing to curb racialization and speculative solutions. The findings were somewhat expected, as the Western publications reflect Western culture of journalism and China Daily, though an English-language publication, is largely a mirror of the Chinese State, even though it is independently operated, researchers said.

“The Chinese paper represents sentiments from a Chinese government point of view, and then the other two papers, which also have a wide readership, give us a global overview,” Abwao said about the selection of publications. “And these newspapers pay attention to social issues and cover them extensively. Also, they tend to set the agenda about social issues in the world.”

Coverage in the most prominent theme of racialization of the virus as a multifaceted threat included numerous inclusions of terms like “Wuhan virus” or “Chinese virus,” pinning the blame on China, and reporting incidences of violence and harassment of Chinese and Asian communities. Within the theme, there was also significant coverage of the blame attributed to the deteriorating China-U.S. relationship during the Trump administration.

COVID-19 as a threat, the second most prominent theme, not only presented coverage that the virus was a threat to health, economics, politics and other aspects of life, but that there was also a subtheme of misinformation. Coverage of politicians and others repeated conspiracy theories that China released the virus to damage other world economies, or that certain countries were happy China was suffering. Such media representation is dangerous, study authors wrote, because even when such information is clearly false, it can potentially bolster such misconceptions in the public mind.

“Broadly, we talk about this as a health crisis, but COVID-19 is not just a health matter. It’s more of a crisis on many different levels. That’s why we also titled the paper ‘a pandemic of hate,'” Ittefaq said. “Pandemics and disease outbreaks have been linked to hate in the past. The COVID-19 crisis emerged as a multifaceted, very complex type of crisis. It is not only financial, cultural, political and social, but also racism has been increased with it and emphasized by right-wing media outlets and politicians. It’s about health, race and xenophobia.”

All newspapers in the sample included coverage in the theme of collectivization to curb racialization of the virus, though it was more prominent in China Daily. That publication even quoted former U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan, who said, “A virus is color blind. It does not discriminate on the basis of skin color, religion or socioeconomic status. It has no ideological bias. It recognizes no national boundaries.” Using the words of Western key individuals was a clear attempt to show that a global crisis was the responsibility of all to address, study authors argue.

The final theme included speculative solutions to end discrimination against people of Asian descent. Coverage therein included calls to support activist groups, harness the power of social media, and hashtags intended to counter discrimination and share messages of solidarity among nations globally.

Study authors used social representations theory (SRT) to understand media coverage of the selected keywords. SRT is primarily a psychology theory: Messages a person hears prominently are very influential in shaping how a person thinks about a certain topic or issue. It applies to mass media, especially in the case of the pandemic, in that the crisis was being widely reported across media. In the messages analyzed from the beginning of the pandemic through 2020, many people were isolated at home, and media was the primary source of information, as people no longer had contact with others they normally share information with.

The findings show the potential danger in naming a disease or health crisis after a geographic location, certain ethnicity or blaming it on certain populations. That has happened repeatedly through history, with “Ebola virus” and the “Spanish flu” as two prominent examples. But even when media is merely reporting the words of prominent politicians or leaders who use xenophobic terms, it influences and shapes global discourse on a topic, thereby potentially leading to or reinforcing discrimination, violence and harassment. The data show it is critical for public health officials, politicians, news media and world leaders to exercise caution when naming, labeling and discussing health crises.

“When something is unknown, people will try to name it. With this being unknown, people started trying to name this virus with names of places,” Abwao said. “People understand and share common ideas through social constructions, so what they construct about an issue, they share. We see here, with COVID-19, the popular view or social construction was this virus is a Chinese virus. This social construction was amplified in the media and in the minds of people, and this is what people tended to believe. SRT suggests the way you name something and anchor it tends to make society think about it in a certain way.”

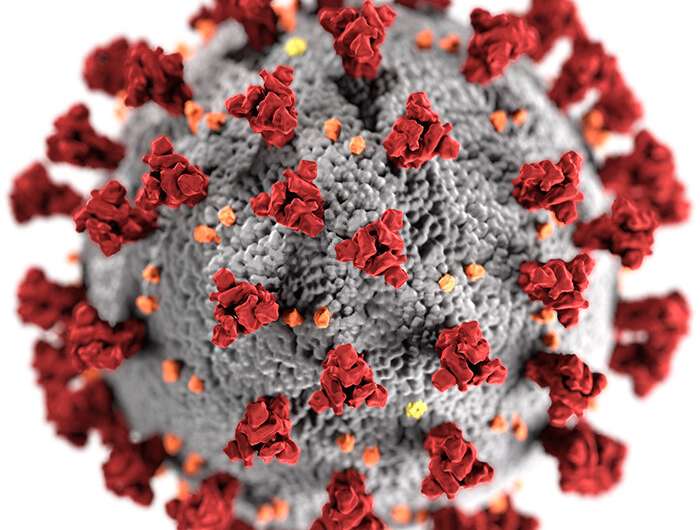

Labels for the COVID-19 virus and its variants have incited xenophobia

Muhammad Ittefaq et al, A pandemic of hate: Social representations of COVID‐19 in the media, Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy (2022). DOI: 10.1111/asap.12300

Citation:

Study finds global media reported pandemic xenophobia, but also emphasized global efforts to fight it (2022, February 10)

retrieved 10 February 2022

from https://phys.org/news/2022-02-global-media-pandemic-xenophobia-emphasized.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

For all the latest Science News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.