Nature’s changing colors makes climate change visible

Following days of torrential rain, more than a dozen rivers in Vermont overflowed in early July, causing catastrophic flooding. Some parts of Vermont saw up to 23 centimeters of rain, or 9 inches, an amount exceeding even the rainfalls from Hurricane Irene in 2011. Once considered 1-in-100-year events, such floods are set to become more frequent as climate change warms the region, scientists say. That’s because warmer air can hold more moisture.

This time, my hometown of Burlington was largely spared. But Lake Champlain, which runs the length of the city, was not. As the water from the Winooski — a 145-kilometer river that swamped the state capital, Montpelier — flows into the lake near where I live, so too does the garbage, gasoline and other pollutants that it swallowed up.

I glimpsed this pollution firsthand while biking with friends on a path along the lake shortly after the worst of the flooding. The south end of the lake, where we started, remained surprisingly clean and free of debris, appearing light blue. But as we biked north, past the junction of river and lake, the water turned murky and brown.

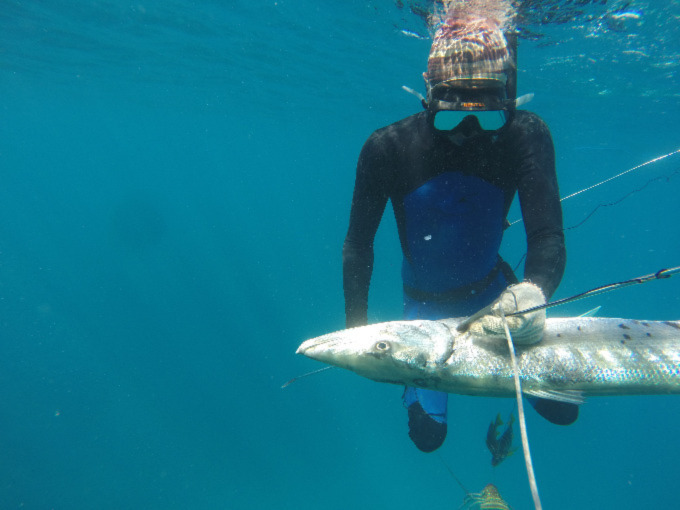

That color shift reminded me of something I’d recently read about deep-sea divers in Estero Salado, a fishing town in the Dominican Republic. The divers describe similar changes to ocean hues where they fish, and their color vocabulary is intricate. They speak of blue, black, yellow, green, purple and chocolate to describe the seawater’s appearance at different times and under different circumstances, writes medical anthropologist Kyrstin Mallon Andrews in July in the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. These colors tell the divers about the state of the water and possible impacts on the behavior and visibility of sea life, such as depth, turbulence and influx of runoff from storms.

Divers also speak of drastic changes to those colors over the years. Purple water, which “surpasses clean,” has become increasingly rare. Yellow water, caused by flooding in the nearby river and toxic runoff from the region’s rice fields, wreaks havoc on once fertile fishing grounds. Longer hurricane seasons turn the waters chocolate brown — a color too dangerous for diving — for months rather than weeks.

My own experience and that of the deep-sea divers made me wonder if using color to describe climate change could work as a communication tool. When I pose the idea to Tim Edensor, a social and cultural geographer at Manchester Metropolitan University in England, he concurs.

Historically, the colors of a person’s world would have stayed fairly constant, he says. But climate change is rapidly altering our visual environment. And those changes can be hard to ignore. “This transformation of the color of the water, I think this is really quite perturbing and it’s also disorienting,” he says.

Such color changes are not limited to our waterways. Scientists have been talking about changes to the world’s color palette for several years. Here in New England, autumn’s vibrant leaves could become duller due, in part, to warmer nighttime temperatures that slow chlorophyll’s degradation process, researchers say. And satellite images show that while much of the Arctic is getting greener, some parts are turning brown, a sign that the vegetation could be dying (SN: 4/11/19).

Many flowers, meanwhile, have increased the amount of their ultraviolet pigments, a natural sunscreen to protect against rising temperatures and a thinning ozone layer, researchers reported in 2020 in Current Biology. While these changes are invisible to the human eye — we can’t see UV radiation — the flowers appear darker to pollinators. That change in hue could reduce a pollinator’s attraction to affected flowers, the researchers wrote.

When it comes to the world’s waterways, satellite images taken over the past 20 years show that over half the world’s oceans have become greener, researchers reported in July in Nature. Dissolved organic material in the water or changes to the type or quantity of phytoplankton are the most likely culprits, says Emmanuel Boss, an aquatic physicist at the University of Maine in Orono. “The bacteria are very happy. There is a whole microbial community that I think is having a blast.”

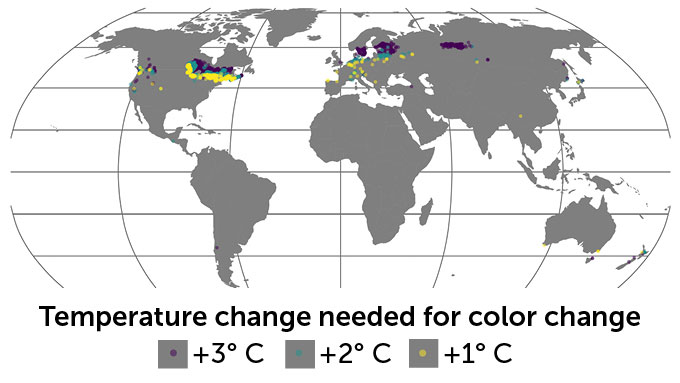

Another study of satellite images found that lakes in areas where average summer temperatures were once moderate and the waters froze come winter are also likely to switch from blue to green or even brown as the climate warms in coming years (SN: 10/3/22). Hot spots for this shift include northern Europe and northeastern North America.

Color changes at such sweeping scales can be hard to grasp. But Mallon Andrews’ research with the Dominican deep-sea divers shows how individuals experience these changes in their communities.

In 2015, Mallon Andrews, of Syracuse University in New York, went to the Dominican Republic to investigate water issues in the region. She spent days standing on a bridge overlooking a bay with the divers and soon learned their ocean language. “Their mode of communicating ocean conditions was always based around color,” she says. “Some colors you can dive in. Some colors have consequences if you dive in them. And some colors are used for navigation purposes.”

As the divers taught her over several years to dive, Mallon Andrews too began to see those nuances in color. She eventually realized that the divers’ color scheme was more than descriptive; it was also diagnostic. Once, for instance, one diver described the water as “methylene blue.” Mallon Andrews had never heard the term, so she looked it up and found that methylene blue is a medication used to treat people suffering from hypoxia. “What he is saying is that previous to these conditions, there was more oxygen in the water,” she says.

Some colors can affect the divers’ physical and mental health, Mallon Andrews says. For instance, because yellow water clouds the water’s surface, the fishermen must dive continually to see fish, an exhausting process. Yellow water also causes skin rashes and debilitating ear infections, along with “sort of generalized angst,” she says.

Pairing that local, firsthand knowledge with more remote monitoring techniques could bring a deeper understanding of how climate change is altering the colors of our world, some scientists say. “It is very valuable for space agencies to have local people take high quality measurements that can be used to validate what we are inferring from space,” Boss says.

The camera on the satellite Boss’ team used to look at the world’s oceans, for instance, can’t see anything smaller than a kilometer, so it lacks detail. Scientists studying those images also have to sift out the material in the atmosphere, such as water vapor, dust and human-made aerosols, to see the ocean with any clarity.

Could learning to read the color of water provide another tool to measure climate change, even for people like me who can barely manage a snorkel? When I pose the question to Brenda Bergman, she is skeptical. People’s subjective look at the water is too variable, says Bergman, who heads the science and freshwater programs for The Nature Conservancy in Vermont. Sensors and direct water readings can do the job more systematically.

But she and Edensor say that helping people become attuned to the world’s changing colors could help them understand how climate change is impacting their local communities.

“A lot of the [climate change] literature is excessively abstract and it’s also unimaginable,” Edensor says. Everyday indicators, like changes to the color of water, are much more tangible.

My bike ride along Lake Champlain was one of these visceral experiences. At first, the kids with us begged to jump into the water. As the water changed color, those requests slowed — then stopped altogether after we spotted seven dead frogs on a rocky outcropping over that murky water.

“These changes can’t be denied,” Edensor says. “You see them with your own eyes.”

For all the latest Science News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.