Naturally fire-prone ecosystems tend to have more species of birds and mammals, study reveals

Wildfires. Many see them as purely destructive forces, disasters that blaze through a landscape, charring everything in their paths. But a study published in the journal Ecology Letters reminds us that wildfires are also generative forces, spurring biodiversity in their wakes.

“There’s a fair amount of biodiversity research on fire and plants,” said Max Moritz, a wildfire specialist with UC CooperativeExtension who is based at UC Santa Barbara’s Bren School of Environmental Science & Management, and is the study’s lead author.

Research has shown that in ecosystems where fire is a natural and regular occurrence, there can be more species of plants—a greater “species richness”—due to a variety of factors, including fire-related adaptations. But, he said, there hasn’t been nearly as much research in the way of animal biodiversity and fire.

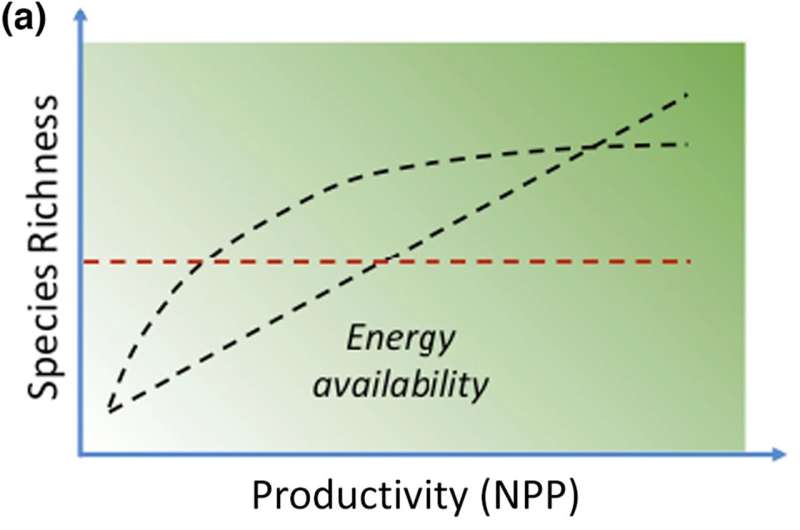

“If you look at how fire operates across the planet, fire actually eats plant productivity,” Moritz said. Productivity, which is a measure of how quickly biomass is generated within a given ecosystem, is also a driver of species richness at broad spatial scales. “When fires occur they can take a bite out of that bottom line,” he added.

If fire regularly consumes some of the base of an ecosystem’s food chain, how does that ripple up to affect the biodiversity at higher levels?

That was the question Moritz investigated during a project supported by UC Santa Barbara’s National Center for Ecological Analysis & Synthesis; he later recruited collaborators Enric Batllori from Universitat de Barcelona and Benjamin M. Bolker from McMaster University in Canada. For several years they combed through global datasets on various factors such as plant biomass, fire observations and species richness patterns.

While it might be natural to assume that plant biomass regularly consumed by fire would in turn lead to lower animal biodiversity, they found that for birds and mammals, fire is associated with increased diversity. In fact, they say, the effect of fire on biodiversity in the case of birds rivals that of the ecosystem’s productivity. And in the case of mammals, fire’s influence was even stronger than that of productivity.

“It’s counterintuitive,” Moritz said. In the short term, fire’s consumption of plant material (also known as “net primary productivity”) could result in less food for the animals that consume plants and make it more difficult to survive and reproduce. But in the longer term, he said, there may be evolutionary effects that unleash adaptations and formations of new species.

The researchers also looked at the effect of fire on amphibian species, however, the connection between fire and biodiversity in their case was difficult to make, possibly because amphibians live in wetter environments where fires may not be a regular occurrence.

So what accounts for the net positive effects of fire on mammal and bird diversity? The study is a correlative one, Moritz said, so more granular examinations have to be made to find out for sure. But it’s likely that fire selects for species that can adapt to and quickly recover from a burn, and fire often creates environmentally complex habitats that meet different species’ requirements.

“We know that fire creates a lot of heterogeneity and opens up all these niches,” Moritz said, and this resource availability might create favorable environments for some organisms to flourish alongside or over others. For example, animals that have strategies to survive fires or reproduce faster might do better in a fire-prone environment, as could those that make use of different habitats that emerge in the wake of a blaze.

Despite the connection between fire and species richness, the authors are careful to point out it does not mean fire is good for all ecosystems. In places where fire is not a natural occurrence, its presence “is more of a modern threat than an important process to maintain,” they said. And for places where fire is a natural part of the ecosystem, climate change-driven and intentional deforestation fires “may be quite different from natural fire regimes.”

Nevertheless, they say, these findings indicate that fire plays an underappreciated role in the generation of animal species richness and biodiversity conservation. Furthermore, the study adds nuance to the Latitudinal Biodiversity Gradient, a global pattern of terrestrial biodiversity in which the world’s most biodiverse areas are located nearest to the equator, with levels of biodiversity generally decreasing toward the poles.

“This is a pattern that people have known for decades and have argued quite a bit about in terms of what drives it,” Moritz said. “And it turns out, it’s hard to figure out. And it looks like fire plays a far more important role than we’ve ever really understood.”

More information:

Max A. Moritz et al, The role of fire in terrestrial vertebrate richness patterns, Ecology Letters (2023). DOI: 10.1111/ele.14177

Citation:

Naturally fire-prone ecosystems tend to have more species of birds and mammals, study reveals (2023, April 13)

retrieved 13 April 2023

from https://phys.org/news/2023-04-naturally-fire-prone-ecosystems-tend-species.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

For all the latest Science News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.