Invading hordes of crazy ants may have finally met their kryptonite

When tawny crazy ants move into a new area, the invasive species is like an ecological wrecking ball—driving out native insects and small animals and causing major headaches for homeowners. But scientists at The University of Texas at Austin have good news, as they have demonstrated how to use a naturally occurring fungus to crush local populations of crazy ants. They describe their work this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“I think it has a lot of potential for the protection of sensitive habitats with endangered species or areas of high conservation value,” said Edward LeBrun, a research scientist with the Texas Invasive Species Research Program at Brackenridge Field Laboratory and lead author of the study.

In some parts of Texas, homes have been overrun by ants that swarm breaker boxes, AC units, sewage pumps and other electrical devices, causing shorts and other damage. Natives of South America, tawny crazy ants have raised alarm bells as they’ve spread across the southeastern U.S. during the past 20 years. The idea for using the fungal pathogen came from observing wild populations of crazy ants becoming infected and collapsing without human intervention.

“This doesn’t mean crazy ants will disappear,” LeBrun said. “It’s impossible to predict how long it will take for the lightning bolt to strike and the pathogen to infect any one crazy ant population. But it’s a big relief because it means these populations appear to have a lifespan.”

Other study authors are Rob Plowes and Lawrence Gilbert at Brackenridge Field Laboratory, and Melissa Jones formerly of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

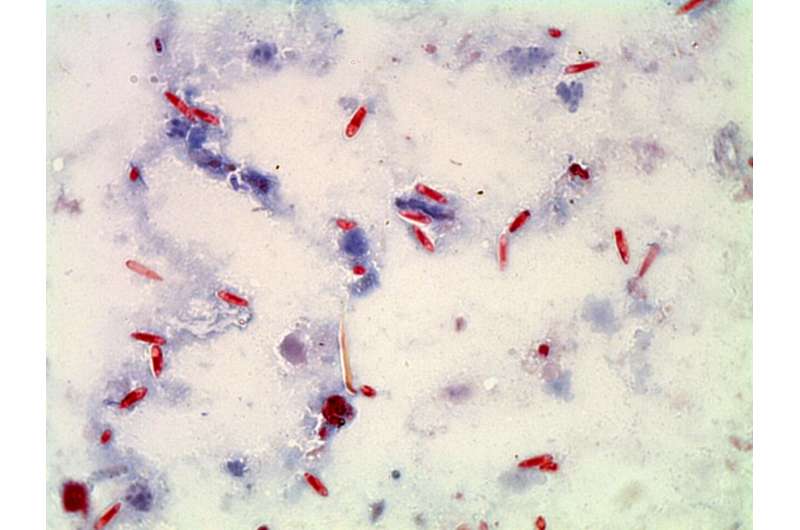

About eight years ago, Plowes and LeBrun were studying crazy ants collected in Florida when they noticed some had abdomens swollen with fat. When they looked inside their bodies, they found spores from a microsporidian, a group of fungal pathogens—a species new to science. Microsporidian pathogens commonly hijack an insect’s fat cells and turn them into spore factories.

It’s not clear where the pathogen came from, perhaps from the tawny crazy ants’ native range in South America or from another insect, but LeBrun and his colleagues started finding the pathogen in crazy ants at sites across Texas. Observing 15 local populations for eight years, the team found that every population that harbored the pathogen declined—and 62% of these populations disappeared entirely.

“You don’t expect a pathogen to lead to the extinction of a population,” he said. “An infected population normally goes through boom-and-bust cycles as the frequency of infection waxes and wanes.”

LeBrun theorizes that perhaps the colonies collapsed because the pathogen shortens the lifespan of worker ants, making it hard for a population to survive through winter.

Whatever the reason, it seems to be a crazy-ants-only problem. Unrelated to other microsporidia that infect ants, the pathogen appears to leave native ants and other arthropods unharmed, making it a seemingly ideal biocontrol agent.

The team deployed the pathogen this way after LeBrun got a call from Estero Llano Grande State Park in Weslaco, Texas, in 2016. The park was losing its insects, scorpions, snakes, lizards and birds to tawny crazy ants. Baby rabbits were being blinded in their nests by swarms of acid-spewing ants.

“They had a crazy ant infestation, and it was apocalyptic, rivers of ants going up and down every tree,” LeBrun said. “I wasn’t really ready to start this as an experimental process, but it’s like, OK, let’s just give it a go.”

Using crazy ants they had collected from other sites already infected with the microsporidian pathogen, the researchers put infected ants in nest boxes near crazy ant nesting sites in the state park. They placed hot dogs around the exit chambers to attract the local ants and merge the two populations. The experiment worked spectacularly. In the first year, the disease spread to the entire crazy ant population in Estero. Within two years, their numbers plunged. Now, they are nonexistent and native species are returning to the area. The researchers have since eradicated a second crazy ant population at another site in the area of Convict Hill in Austin.

The researchers plan to test their new biocontrol approach this spring in other sensitive Texas habitats infested with crazy ants.

Invasive tawny crazy ants have an intense craving for calcium – with implications for their spread in the US

Pathogen-mediated natural and manipulated population collapse in an invasive social insect, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2114558119

Citation:

Invading hordes of crazy ants may have finally met their kryptonite (2022, March 28)

retrieved 28 March 2022

from https://phys.org/news/2022-03-invading-hordes-crazy-ants-met.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

For all the latest Science News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.