How A Neon White Level Is Made

Introduction

As of writing, the fastest runthrough of Neon White’s “Smackdown” level is 9.56 seconds, earned by player “earlobe” on September 6, 2022.

Standing in contrast is the work that went into it. According to designer and creative director Ben Esposito, the earliest iteration was in March 2019, more than three years before its release in June 2022. In that time, there were more than 50 different iterations. Sometimes changes were small. Other times they fundamentally altered the level. Every designer who worked on the game has touched Smackdown in some form. Nevertheless, load into it now; chances are all that labor is invisible to you. Before sitting down to write, I beat it in just 11 seconds.

Neon White is a game built around speedrunning. Levels are short. If you’re playing as intended, you hardly notice your surroundings before moving on. But the only way that works effectively is if levels are meticulously designed to facilitate that movement; they have to be made so that it feels natural for the player to fly through them. Making a level you barely think twice about takes a lot of effort.

Largely, it works. We gave Neon White a 9.5, and our review mentioned the level and game design, saying it feels “effortless as if you’ve practiced for years, not just 15 to 20 minutes.”

To understand how that effortlessness was achieved, we talked to Esposito, game/level designer, programmer Russell Honor, and senior level designer and environment artist Carter Piccollo, who walked us through the making of Smackdown from concept to completion.

March 2019

March 2019

Neon White is about speedrunning. But it wasn’t always the case that every level emphasized that point.

As Esposito tells it, before Smackdown, a lot of levels were built around the idea of teaching specific mechanics. But when work on Smackdown started, it was the first time the team tackled the idea of repeatedly playing through an individual level, optimizing times, and discovering different paths and shortcuts. Of course, Neon White still teaches you its mechanics, but Smackdown caused the team to re-look at the game as a whole.

“This was specifically about exploring, ‘What if we didn’t teach you something new? What if it was about revisiting it over and over again,’” Esposito says. “And the things we ended up learning in levels like this created new ways of thinking about the rest of the game.”

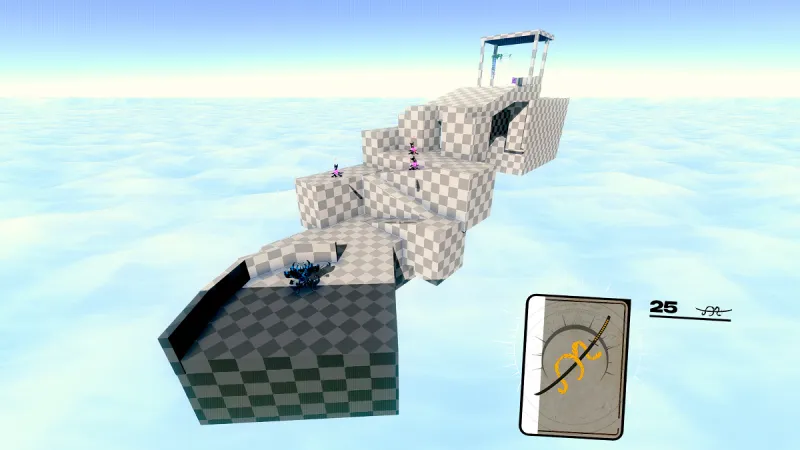

He pulls up the earliest version, running in the game engine Unity. It’s a graybox, featuring the level geometry but without any art (see picture). While a few core ideas are the same as the shipped version – some enemy placements and level layout – there is one immediate flaw: ambiguity. It’s not always clear what you need to do.

In this iteration, the level begins with a Godspeed card and an enemy standing to the right. It’s telling the player to grab the card, which grants a dash forward, before killing the enemy, which then drops an Elevate card, giving a double jump. But as Piccollo points out, there’s nothing on which to use that Elevate card. Neon White, he says, is all about using what you immediately have.

To cut ambiguity, they’ll need to remove the Elevate card, telling the player instead they need to jump to the left (not double jump, mind you) and then dash forward through the next set of enemies. However, that dash also presents its own set of issues. Two enemies stand on opposite sides of a small gap, and by the time you reach them, you have two Godspeed cards. The enemies are placed so the player has to dash through both, but it’s unclear if they must dash twice to kill them or if one will do the trick.

This issue is a core problem.

“If you’re ever confused on what to do, the game doesn’t feel good and it starts to fall apart,” Piccollo says. “Your first time through needs to feel really clear. And the time where you’re fully optimized also needs to feel really good, otherwise it feels like you’re doing it wrong, even if it’s faster.”

Removing ambiguity, Esposito says, was the main work of building levels. The less ambiguous, the more confident a player feels. The more confident, in this case, the more fun they have.

Honor and Esposito both point to a card placed in this early version. It’s a Bomb card only used for shortcuts. Which in that specific context works, but ideally, the player won’t know or see the shortcut on their first runthrough. It means this card is useless in the rest of the level. That undercuts the player’s confidence.

“People would pick up the card and not understand what they were expected to do with it [and think they] missed something,” Esposito says. “That was another rule that we had to establish; every card has to have an obvious purpose in the moment that you pick it up.”

May 2020

May 2020

We jump forward in time 14 months, seeing a later iteration from May 2020. The most noticeable change is all the art; it’s beginning to look like Neon White.

There’s now a straight runway at the beginning, funneling the player into the level. It features both a Godspeed and an Elevate card, though it’s laid out in such a way that you can’t see the latter behind the former. It’s a problem that’s addressed in later versions.

Issues from the first iteration also show up here — the dash is still unclear, it’s not immediately apparent what cards you should use, and as Esposito says, “there’s a lot going on.”\

But the first half of Smackdown is starting to take shape. The back half is a different story; it’s completely different from the shipped version. Esposito points out a “failed” experiment where an enemy stands behind metal bars. The idea is players can shoot through these bars to kill an enemy, but can’t go through themselves. The setup still shows up in different forms throughout the game, but in this case, it’s cut. “Just because it was a confusing concept to people,” Esposito says. “It felt so important but it was actually completely unimportant to the concept of the level that it was distracting everyone.”

There’s no average number of changes or tweaks between iterations; it ranges from small nudges to complete remakes. That said, quick math reveals the scale of Neon White’s development. If we consider that it shipped with over 100 levels, the team made “double” that amount in scrapped levels, and Smackdown alone had more than 50 changes made to it, we’re faced with thousands of tweaks and redesigns throughout the entire game. Neon White is made to play as fast as possible, but getting it to that point was a long, monumental task.

Additionally, the team came up with new ideas later in development and re-added them to the entire game. Smackdown, which was worked on from the very beginning to nearly the end, was one such level. It worked as a prototype for a Neon White stage and what it needed to be successful. That influenced the rest of the game and required new lessons to be reapplied throughout the whole of Neon White.

We jump ahead to January 2021. The runway is fixed, both beginning cards are perfectly visible. The first enemy to the right from earlier no longer drops a card. The dash still needs work, but it’s getting closer. In the middle, there’s an enemy at the top of the staircase, but you might miss that fact at first glance. The ending is close to the final version, maybe in a shippable state, but still a bit clunky.

Eight months later, and the two cards at the beginning are spaced further apart to allow the player more reaction time. The gap is much longer to make it clear you need two dashes to get both enemies. The enemy atop the staircase now shoots down at you, so you can see its location. Across the board, Smackdown is now giving the player more information, making it easier to navigate. It’s becoming unambiguous. The ending is falling into place, but the pathing to the optional gift is unclear. It’s reachable by jumping atop the columns surrounding the back of the level. But where the player needs to do that isn’t, as Esposito calls it, inviting. It looks like a place the player isn’t meant to reach.

But Smackdown is almost complete. And in a few more months, it’ll be shippable.

March 2022

March 2022

Honor’s last change was on March 5, 2022. Esposito’s last bug fix was on March 27. He doesn’t specify, but Esposito says this final version is full of small tweaks. The art is finalized and the whole thing looks like the Smackdown you may know.

The most significant change is the gift at the end. It’s now far clearer there’s a path around the back of the level leading to its hiding spot; it looks like part of the stage now, not a background element. Finally, two wooden planks are placed in the direction of the gift as a final nudge to the player.

Three years later, Smackdown is complete.

It’s impossible to run down every tweak and change made throughout the level’s development. Sadly, there was a lot we had to leave out, and almost certainly dozens of things the team didn’t have time to go over with us. Nevertheless, an overview of three years of development distilled through the lens of one short level — even one completable in mere seconds — highlights the sheer scale of game development at all sizes. Neon White is a game made to be played quickly; it’s digestible in short chunks. Its development was anything but.

From entire redesigns to minor additions players won’t think twice about, it’s about the sum total of its parts than any one thing.

Unless you’re Honor, who boils Smackdown’s success down to one tiny decision.

“I think when those two planks got put down, that’s when it went from kind of a bad level to just about perfect,” he jokes.

This article originally appeared in Issue 350 of Game Informer.

For all the latest Gaming News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.