Heart failure risk rises in men as they lose Y chromosome with age, study finds

Loss of the Y chromosome in the blood cells of men as they age can cause impaired heart function and death from cardiovascular diseases, according to a new study that may lead to novel therapies to treat heart ailments.

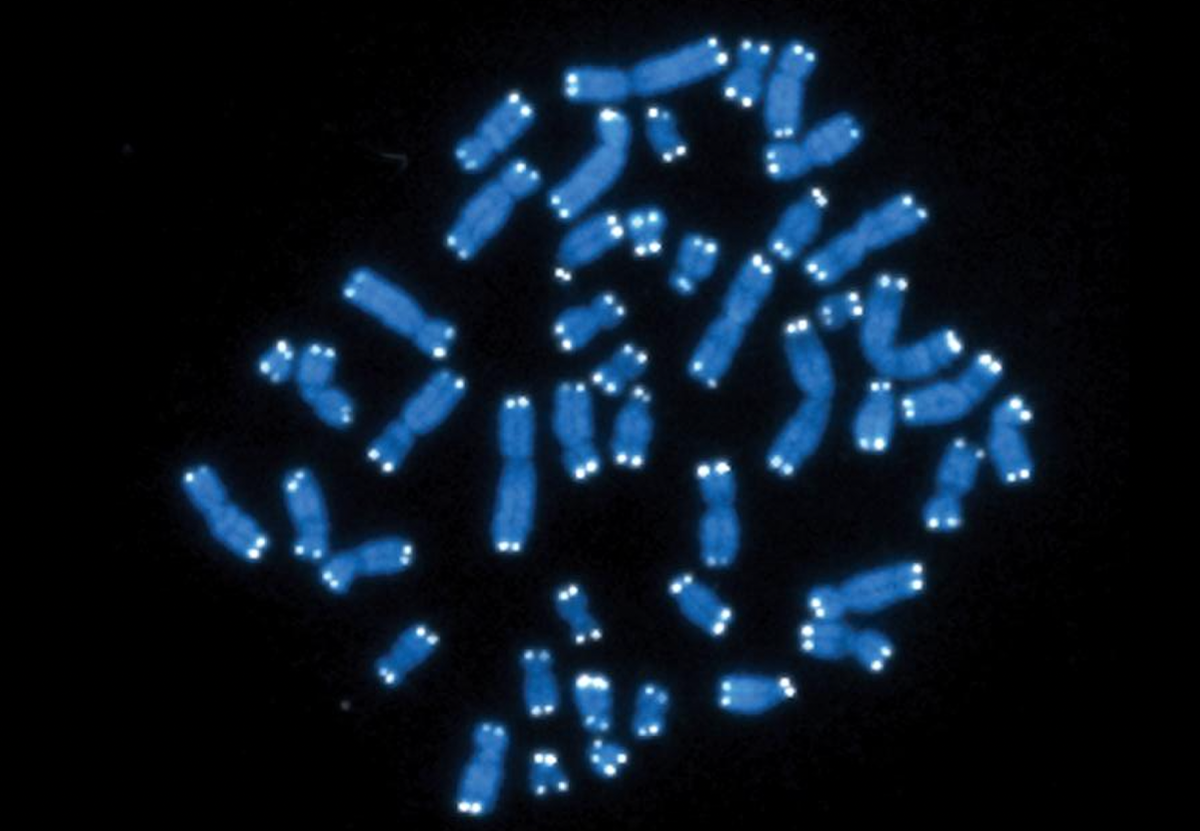

Previous research has shown that men, on average, die several years younger than women, with the gradual loss of Y chromosome in their immune system’s white blood cells linked to an increased risk of developing diseases like cancer and Alzheimer’s.

The new research, published in the journal Science on Thursday, found that those with such Y chromosome loss, called mLOY (mosaic Loss Of Y) in the white blood cells also have an increased risk of dying from heart diseases, the most common cause of death in humans.

Researchers, including those from Uppsala University in Sweden, say until now it was unknown whether mLOY in the white blood cells has a direct effect on disease progression in other organs.

“The DNA of all our cells inevitably accumulate mutations as we age. This includes the loss of the entire Y chromosome within a subset of cells within men. Understanding that the body is a mosaic of acquired mutations provides clues about age-related diseases and the aging process itself,” said study co-author Kenneth Walsh from the University of Virginia.

In the new study, scientists used the gene-editing tool Crispr to generate mouse models with mLOY in their white blood cells.

They found that mLOY caused direct damage to the rodents’ internal organs and that mice with mLOY had a shorter survival than those without mLOY.

“In the mouse models used in the study, the mouse Y chromosome was eliminated to mimic the human mLOY condition and we analysed the direct consequences that this had. Examination of mice with mLOY showed an increased scarring of the heart, known as fibrosis,” Lars Forsberg, a co-author of the study at Uppsala University, said in a statement.

“We see that mLOY causes the fibrosis which leads to a decline in heart function,” Dr Forsberg said.

When researchers compared the observed effect in mice with population studies in humans, they found mLOY to be a new significant risk factor for death from cardiovascular disease in men.

The comparative study assessed data from UK Biobank – a database with genomic and health information from half a million normally aging individuals who were between 40 and 70 years old at the start of the study.

Scientists found that men with mLOY in their blood at the start of the study displayed an approximately 30 per cent increased risk of dying from heart failure and other types of cardiovascular disease during approximately 11 years of follow-up.

“We also see that men with a higher proportion of white blood cells with mLOY in the blood have a greater risk of dying from cardiovascular disease. This observation is in line with the results from the mouse model and suggests that mLOY has a direct physiological effect also in humans,” Dr Forsberg said.

The study suggests mLOY in a certain type of white blood cell in mice heart, known as cardiac macrophages, stimulates a molecular pathway that leads to increased fibrosis.

It describes for the first time a mechanism by which mLOY in blood causes disease in other organs and further identifies a possible treatment.

When researchers blocked the molecular pathway, the pathological changes in the heart caused by mLOY could be reversed.

“The link between mLOY and fibrosis is very interesting, especially given the new treatment strategies for heart failure, pulmonary fibrosis and certain cancers that aim to counteract the onset of fibrosis. Men with mLOY could be a patient group that responds particularly well to such treatment,” Dr Forsberg said.

“Studies that examine Y chromosome loss and other acquired mutations have great promise for the development of personalised medicines that are tailored to these specific mutations,” Dr Walsh added.

For all the latest Science News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.