Bringing the field to students with ‘Virtual Field Geology’

University of Washington geologists had set out to create computer-based field experiences long before the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Juliet Crider, a UW associate professor of Earth and space sciences, first sent a former graduate student and a drone to photograph an iconic Pennsylvania geological site and pilot a new approach to field geology.

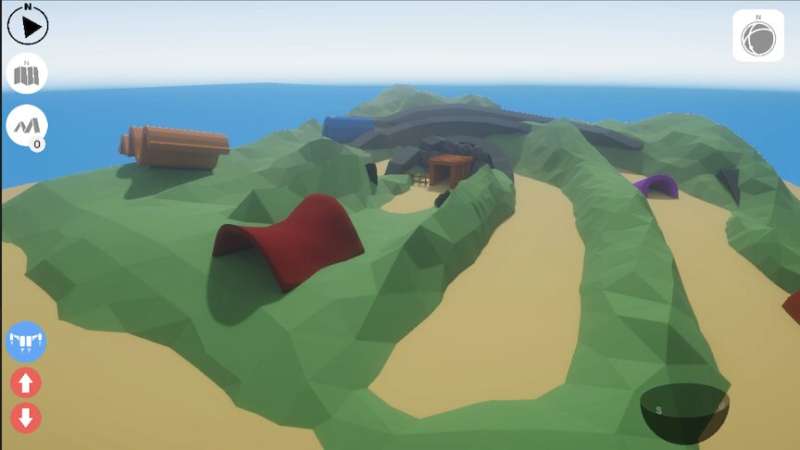

Her team has now completed a virtual field visit to that site, the Whaleback anticline, where decades of coal mining have exposed 300-million-year-old folds in the bedrock. A pilot version of the web-based tool was used during the pandemic, and a version that allows people to wear virtual reality headsets to explore the geological site just launched. A UW field class used both tools in an undergraduate summer course that for the first time blended virtual and in-person field trips.

The UW Virtual Field Geology project has many goals: to make geology field experiences accessible to more people; to document geological field sites that may be at risk from erosion or development; to offer virtual “dry run” experiences that complement field courses and help new students acclimate to the field; and to allow scientific collaborators to virtually visit a field site and explore it together.

Max Needle, a UW doctoral student in Earth and Space Sciences, used his background in geology to help develop the virtual field experiences. He is lead author of a paper published in Geoscience Communication that presents the first two sites: the Whaleback site and a fictional site called “Fold Islands.”

“Virtual experiences provide access to more people, they let us visit sites that are completely inaccessible, and we think everyone can benefit from a new way to interact with the tools of field geology,” Needle said.

Last summer, instead of the traditional UW geology six-week field course in Montana, the department held a hybrid version led by Crider and Cailey Condit, a UW assistant professor of Earth and space sciences. It combined classroom teaching and digital experiences with day trips to the many geologic sites within driving distance of the Seattle campus.

“Moving forward, these virtual field trips are likely going to play a key part in making the geosciences more accessible and more equitable,” Condit said. “They provide the opportunity for all students to be able to begin experiencing fieldwork remotely, and learn about how vital the geologic field context is for the geosciences.”

The pandemic altered the project’s trajectory. When COVID canceled field trips, the team put the virtual reality programming on pause and focused on creating a web-based version that would be accessible most quickly to the most people. Since the site launched, it’s been accessed more than 1,700 times by UW undergraduates and, after sharing among the geology teaching community, around the world. The team recently completed the VR version.

Even though people can now travel and assemble, the team believes virtual experiences could become part of a “new normal” for geology research and education.

“Part of increasing access to the field is to help people know what to anticipate,” Crider said. “To the extent that we can help students anticipate both the outdoors experience and the science experience, then the uncertainty and maybe anxiety is reduced, and people can focus on the learning goals.”

The virtual experiences allow people to visit the field site and use common geology tools to measure angles in the rock layers or orientation of cracks that explain a landscape’s history. While a virtual option benefits anyone challenged by the travel and access to a remote field site, it also lets all students and researchers have a “dry run” experience and review techniques before reaching the actual location.

In the web-based virtual experience, keyboard commands let a user walk across the landscape. Users can try various tools to measure distances and angles. Selecting three points creates a virtual plane and displays its orientation. Data can be downloaded into a spreadsheet or directly into a popular geology software program.

“What’s unique about this experience is that it’s open-ended, which allows instructors to tailor the lessons and the goals,” Crider said. “Students decide what to measure, and where to measure, to answer the questions—it’s not predetermined. Making those decisions is an important thing to learn.”

The virtual experience also gives the scientist superhuman powers to instantly swoop from one place to another, zoom in and out to explore a site at different scales.

“One of the cool advantages of the game is that you can fly. There’s a little jetpack icon and then you go up in the air, and all of a sudden your perspective changes, and you can travel quickly from place to place,” Needle said.

It also provides access to sites that have limited or risky access.

“At the Whaleback anticline a lot of the interesting, curved rock geometry is exposed at a height of 30 feet, where you can’t walk without risking fatality,” Needle said.

The team recently demonstrated the virtual reality version of the Pennsylvania site. Although VR requires a special headset, the field of view is larger, and VR offers a sense of scale that’s helpful at sites like the 30-foot-tall Whaleback anticline. An interactive feature lets the user pick up a rock hammer and split open a 3-D model of a rock.

“As a teaching assistant, I’ve seen students confronted with challenges in the field that go beyond the academic aspect,” Needle said. “Or maybe someone can’t go into the field because they have bad asthma, or a particular field site can only be accessed with specialized climbing gear. We think a lot of people can benefit from these tools.”

Needle ran a short course at the Geological Society of America’s annual meeting in October showing other geologists how to use the UW software to create other virtual field visits. This was the third such workshop he’s given, and the largest so far. All the software used for the UW experiences are freely available.

Projects are under way for sites in Pennsylvania, Vermont and California. Needle hopes that someday the software might be used to visit the bottom of the ocean or the surface of another planet.

“I think this is a prototype of where the field of geology could be headed in the future,” Needle said.

More information:

Mattathias D. Needle et al, Virtual field experiences in a web-based video game environment: open-ended examples of existing and fictional field sites, Geoscience Communication (2022). DOI: 10.5194/gc-5-251-2022

Citation:

Bringing the field to students with ‘Virtual Field Geology’ (2022, December 13)

retrieved 13 December 2022

from https://phys.org/news/2022-12-field-students-virtual-geology.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

For all the latest Science News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.