Bison spread as Native American tribes reclaim stewardship

Perched atop a fence at Badlands National Park, Troy Heinert peered from beneath his wide-brimmed hat into a corral where 100 wild bison awaited transfer to the Rosebud Indian Reservation.

Descendants of bison that once roamed North America’s Great Plains by the tens of millions, the animals would soon thunder up a chute, take a truck ride across South Dakota and join one of many burgeoning herds Heinert has helped reestablish on Native American lands.

Heinert nodded in satisfaction to a park service employee as the animals stomped their hooves and kicked up dust in the cold wind. He took a brief call from Iowa about another herd being transferred to tribes in Minnesota and Oklahoma, then spoke with a fellow trucker about yet more bison destined for Wisconsin.

By nightfall, the last of the American buffalo shipped from Badlands were being unloaded at the Rosebud reservation, where Heinert also lives. The next day, he was on the road back to Badlands to load 200 bison for another tribe, the Cheyenne River Sioux.

“Buffalo, they walk in two worlds,” said Heinert, 50. “Are they commercial or are they wildlife? From the tribal perspective, we’ve always deemed them as wildlife, or to take it a step further, as a relative.”

Now 82 tribes across the U.S. have more than 20,000 bison in 65 herds—and that’s been growing along with the desire among Native Americans to reclaim stewardship of an animal their ancestors depended upon for millennia.

European settlers destroyed that balance, driving bison nearly extinct until conservationists including Teddy Roosevelt intervened to reestablish a small number of herds.

The long-term dream for some Native Americans: return bison on a scale rivaling herds that roamed the continent in numbers that shaped the landscape itself. Heinert, a South Dakota state senator and director of the InterTribal Buffalo Council, views his job more practically: Get bison to tribes that want them, whether two animals or 200.

“All of these tribes relied on them at some point,” he said. “Those tribes are trying to go back to that, reestablishing that connection.”

Bison for centuries set rhythms of life for the Lakota and other nomadic tribes. Hides for clothing and teepees, bones for tools and weapons, horns for ladles, hair for rope—a steady supply of bison was fundamental.

At so-called “buffalo jumps.” herds would be run off cliffs, then butchered over days and weeks.

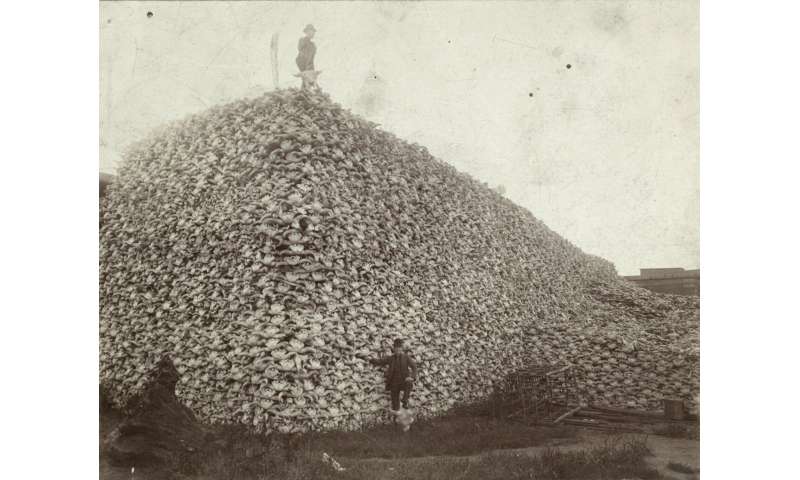

European settlers brought a new level of industry to the enterprise—and bison killing dramatically increased, their parts used in machinery, fertilizer and clothing. By 1889, only about 1,000 remained.

“We wanted to populate the western half of the United States because there were so many people in the East,” U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American cabinet member, said in an interview. “They wanted all of the Indians dead so they could take their land away.”

The thinking at the time, she added, was “‘if we kill off the buffalo, the Indians will die. They won’t have anything to eat.'”

The day after the bison transfer from the Badlands, Heinert’s son T.J. had his rifle fixed on a large bull bison at the Wolakota Buffalo Range. The tribal enterprise in just two years has restored about 1,000 bison to 28,000 acres (11,300 hectares) of rolling, scrub-covered hills near the Nebraska-South Dakota border.

The 28-year-old had talked all morning about the need for a perfect shot in 40-mile (64-kilometer) an hour winds. The first bullet went into the animal’s ear, but it lumbered away a couple hundred yards to join a larger group of bison, with the hunter following in an all-terrain vehicle.

After the animal finally went down, Heinert drove up close, put the rifle behind its ear for a shot that stopped its thrashing.

“We got him down,” he said. “That’s all that matters.”

The Rosebud Sioux are intent on expanding the reservation’s herds as a reliable food source.

Others have grander visions: The Blackfeet in Montana and tribes in Alberta want to establish a “transboundary herd” ranging over the Canada border near Glacier National Park. Other tribes propose a “buffalo commons” on federal lands in central Montana where the region’s tribes could harvest animals.

“What would it look like to have 30 million buffalo in North America again?” said Cristina Mormorunni, a Métis Indian who’s worked with the Blackfeet to restore bison.

Haaland said there’s no going back completely—too many fences and houses. But her agency has emerged as a primary bison source, transferring more than 20,000 to tribes and tribal organizations over 20 years.

Transfers sometimes draw objections from cattle ranchers who worry bison carry disease and compete for grass. Yet demand from the tribes is growing, and Haaland said the transfers will continue. That includes about 1,000 bison trucked this year from Badlands, Grand Canyon National Park and several national wildlife refuges.

-

![Bison spread as Native American tribes reclaim stewardship]()

T.J. Heinert, assistant range manager of Wolakota Buffalo Range near Spring Creek, S.D., inspects the bull bison he harvested on Friday, Oct. 14, 2022. Credit: AP Photo/Toby Brusseau

-

A herd of bison roam the prairie landscape at the Wolakota Buffalo Range near Spring Creek, S.D. on Friday, Oct. 14, 2022. The range stretches over 28,000 acres and is home to over 1,000 buffalo. Credit: AP Photo/Toby Brusseau

-

![Bison spread as Native American tribes reclaim stewardship]()

Daniel Eagle Road of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, left, and T.J. Heinert, assistant range manager of Wolakota Buffalo Range, prepare a bull bison for butchering as Rosebud community members and visitors from other tribes gather to assist on Friday, Oct. 14, 2022. (AP Photo/Toby Brusseau

-

In this 1892 photo made available by the Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library, a man stands atop a pile of buffalo skulls as another rests his foot on one at a glue factory in Rougeville, Mich. Credit: Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library via AP

-

![Bison spread as Native American tribes reclaim stewardship]()

Margaret O’Connor of the Inupiaq Tribe in Alaska holds holds back the buffalo’s hide as others begin the butchering process during a harvest at the Wolakota Buffalo Range near Spring Creek, S.D., on Friday, Oct. 14, 2022. Credit: AP Photo/Toby Brusseau

-

Margaret O’Connor describes how to trim fat from a piece of bison that was shot and butchered at the Wolakota Buffalo Range on the Rosebud Indian Reservation, Oct. 14, 2022, near Spring Creek, S.D. Credit: AP Photo/Matthew Brown

-

![Bison spread as Native American tribes reclaim stewardship]()

Knives and a sharpener sit on the bed of a truck at the Wolakota Buffalo Range near Spring Creek, S.D., on Friday, Oct. 14, 2022. The knives were used to butcher a buffalo harvested. Credit: AP Photo/Toby Brusseau

-

Meat from a buffalo that’s been butchered and packaged is shown at the Wolakota Buffalo Range, on Oct. 14, 2022, near Spring Creek, S.D. More than a dozen people took part in butchering the bison after it was harvested earlier that day. Credit: AP Photo/Matthew Brown

-

![Bison spread as Native American tribes reclaim stewardship]()

Children on the Rosebud Indian Reservation help process meat from a bison that was shot and butchered at the Wolakota Buffalo Range, Oct. 14, 2022, near Spring Creek, S.D. Credit: AP Photo/Matthew Brown

-

A buffalo hide is spread on a railing as it is scraped and cleaned by, from left, Natalie Bordeaux, Foster Cournoyer-Hogan, Hollie Mackey and Madonna Sitting Bear at the Wolakota Buffalo Range on the Rosebud Sioux Reservation, near Spring Creek, S.D. The four were helping process the half-ton bison that had been shot earlier in the day. Credit: AP Photo/Matthew Brown

-

![Bison spread as Native American tribes reclaim stewardship]()

Cliff Moran uses a flag to coax bison out of a trailer as the Rosebud Indian Reservation’s buffalo coordinator, Wes Plank, looks on, after the animals were delivered from Badlands National Park, on Oct. 13, 2022, near Soldier Creek, S.D. The Rosebud reservation is home to three herds of the animals that are used for food and in ceremonies, part of an effort to revive traditions nearly stamped out during decades of forced assimilation. Credit: AP Photo/Matthew Brown

-

A lone buffalo races across the prairie at the Wolakota Buffalo Range near Spring Creek, S.D., on Friday, Oct. 14, 2022. The Wolakota Range is home to over 1,000 buffalo. Credit: AP Photo/Toby Brusseau

Back at Wolakota range, Heinert sprinkled chewing tobacco along the back of the bison he’d just shot and prayed. Then the half-ton animal was hoisted onto a flatbed truck for the bouncy ride to ranch headquarters.

About 20 adults and children gathered as the bison was lowered onto a tarp.

“This relative gave of itself to us, for our livelihood, our way or life,” said tribal elder Duane Hollow Horn Bear.

Soon the tarp was covered with bloody footprints from people butchering the animal. They quartered it, sawing through bone, then sliced meat from the legs, rump, and the animal’s huge hump. Children, some only 6, were given knives to cut away skin and fat.

Katrina Fuller, who helped guide the butchering, dreams of training others so the reservation’s 20 communities can come to Wolakota for their own harvest. “Maybe not now, but in my lifetime,” she said. “That’s what I want for everyone.”

© 2022 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.

Citation:

Bison spread as Native American tribes reclaim stewardship (2022, November 21)

retrieved 21 November 2022

from https://phys.org/news/2022-11-bison-native-american-tribes-reclaim.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

For all the latest Science News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.