The revealing history of Birkenstock sandals

It’s proof of popularity that the German footwear brand Birkenstock never wanted. In the fight against fakes, the shoemaker has been sending teams of undercover investigators with hidden cameras into what they say are counterfeiting factories.

Birkenstock’s CEO Oliver Reichert is aggressive. “We don’t just punish the marketplaces or the resellers. We really go to the factories. Turkey, Philippines, China, wherever.”

“Sounds like you’re running special ops,” said correspondent Seth Doane.

“Yes, but that’s necessary.”

Birkenstock

His unconventional approach is clear at their Munich headquarters. Doane said, “You were sitting at your desk listening, at times blasting, music. It’s not what you’d expect from a CEO.”

“Probably I’m not the average CEO,” Reichert said. “I never tried to be average in anything.”

And Birkenstock has proved it’s not average, either. If you haven’t noticed, Birkenstocks are everywhere, revealing the toes (or, yes, socks) of not just the most unfashionable among us, but models and celebrities, too. It’s undeniable that Birkenstock is having a moment, nearly 250 years in the making.

And “Birks” have come a long way from their days as a hippie staple.

CBS News

Since he took over this formerly family-run business in 2009, Reichert has tried to inject a “startup” energy. “If you have such a tradition and such a history, the threat is to wake up in your own museum,” he said, “and I don’t want to have this.”

He’s ruthless regarding brand-collaboration requests. They get plenty. “Eight out of ten, we say no.”

They said “yes” to Dior, and are now producing a felt-covered shoe.

Doane asked, “How much is this?”

“Not enough, I would say,” Reichert replied.

It’s retailing for over $1,000.

“It’s about supporting the idea behind the product and not harming the DNA of either brand,” he said. “It’s like a marriage, you know?”

And there’s luxury shoemaker Manolo Blahnik, known for his coveted stilettos. Blahnik, an avid Birkenstock customer, is now a collaborator.

CBS News

Doane said, “You think of Manolo Blahnik in ‘Sex and the City’ and Sarah Jessica Parker.”

“Yeah, yeah, but she’s wearing Birkenstocks as well, even in the private life,” said Reichert.

“When you see some celebrity pictured with Birkenstocks, what do you think?”

“I’m proud that they’re wearing Birkenstocks, and I know – and this makes me even prouder – they buy for it.”

“You don’t give them to some famous person?”

“No. We don’t have a Hollywood office or something like this.”

“And if some celebrity says, ‘Hey, I’ll wear this shoe,’ you won’t send them a shoe?”

“Why?”

“Come on!”

“If they send me money, I will send them a shoe!” Reichert said.

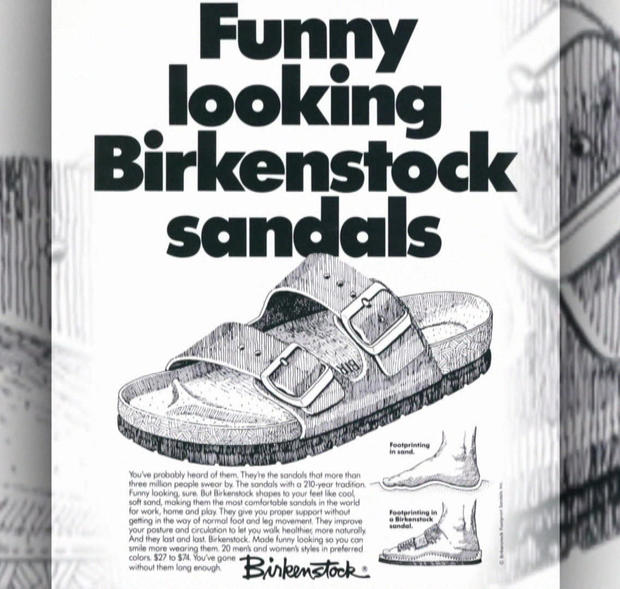

It’s a glamorous twist for a company that traces its roots back to a cobbler in central Germany in 1774. In the late 1800s, a descendant, Konrad Birkenstock, began making and selling flexible insoles. For decades that humble “footbed” was the family business.

Reichert said, “In the Sixties, Carl Birkenstock was somehow frustrated that, ‘OK we make the best insole in the world, but nobody sees our product.’ So, he decided to try to bring the footbed out of the shoes, and that’s the birthday of the sandal.”

CBS News

“But the shoe stores in America didn’t want the product?” said Doane.

“It was the ‘ugly shoe’! You know, they say, ‘Oh, OK, are you crazy?'”

Ugly, perhaps, and for a time uncool. But in just the past decade, Birkenstock reports sales have more than quadrupled, with the most popular model being the Arizona.

Then, COVID provided another unexpected boost: “Unfortunately, we became the number one home office shoe,” Reichert said. Online demand was “crazy.”

“So, why do you say ‘unfortunately’?”

“It’s painful to have no sales, but it’s very painful to have too much sales, trying to manage this global demand. It’s challenging.”

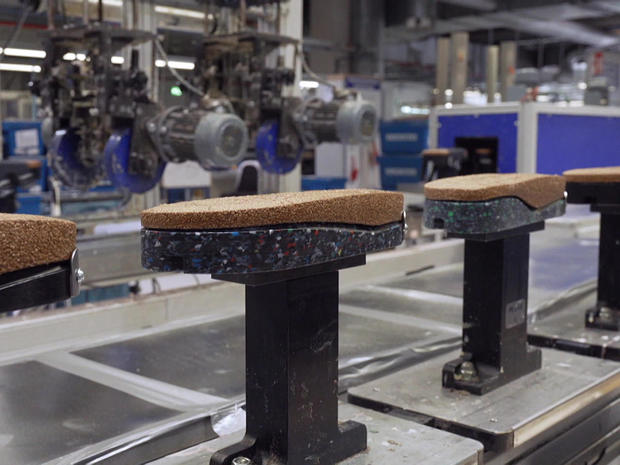

Doane saw that at one of their factories in the east of Germany, where they were racing to fill a backlog of nearly a million pairs.

Managing director Hilmar Knoll juggles the logistics. “We have here stock only for ten days,” he said. “We’re always at the limit of our capacity.”

Daily, they produce 80,000 footbeds, which all start as a mix of cork from Portugal. Their “secret recipe” of jute, cork, latex and leather is heated, then squeezed into molds.

CBS News

Birkenstock still makes all its shoes in Germany, and is fiercely protective of that quality. As part of its effort to crack down on counterfeiters, it stopped selling on Amazon, citing the number of fakes being sold.

How hard was that? “For us, nothing,” said Reichert.

“Well, it’s a huge outlet!” said Doane.

“Maybe, but not a good one. I think at the beginning Amazon was a pioneer in online trading. You have to kill monsters when they are small. They’re getting too big? You can’t kill them, okay? They will eat you. And we decided to kill our monsters early.”

In a statement, Amazon told “Sunday Morning,” “Fewer than 0.01% of all products sold on Amazon received a counterfeit complaint from customers and we won’t rest until that number is zero.”

The robust market for fakes reinforces (as if anyone needed a reminder) just how popular these sandals are, whatever the reason: “Even the people who hate the brand wear them because they are good,” said Reichert. “It’s like, you know, do you like taking medicine? No. It helps! So, you swallow it.”

Doane said, “You seem almost proud that some people don’t like your product?”

“It’s a proof of concept. It doesn’t matter for us, because once you get the product, you will wear this, and you re-buy it. So, you know, one day we’ll get you.”

For more info:

Story produced by Mikaela Bufano. Editor: Brian Robbins.

For all the latest World News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.