Researchers find eleven million-year-old fossils in southern Germany’s Hammerschmiede clay pit

Researchers from the Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum in Frankfurt and the Senckenberg Center for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment at the University of Tübingen have discovered the fossil remains of a previously unknown species of prehistoric waterfowl in the Hammerschmiede clay pit. Allgoviachen tortonica, as the researchers named the new species, populated the southern German region around eleven million years ago. The findings suggest that these birds lived not only on the ground, but also in trees, and were about the size of modern-day Egyptian geese. The researchers’ study was recently published in the journal Historical Biology.

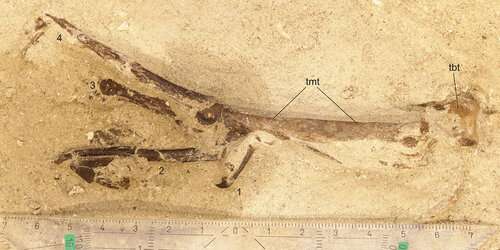

The find was made during excavations in 2020. The unusual thing about it is the completely preserved leg. Professor Madelaine Böhme of the Senckenberg Center for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment at the University of Tübingen says, “Such complete finds are very rare for fossil waterfowl worldwide.” Particularly revealing about the lifestyle of Allgoviachen tortonica is the shape of its claws.

These differ markedly from the claws of modern-day waterfowl, which have a predominantly swimming lifestyle, explains the head of the study, Dr. Gerald Mayr of the Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum in Frankfurt. The researchers conclude that the ancient birds had powerful tendons that helped them to strongly flex their claws. “Such claw flexion allows them to cling to branches or logs floating in the river. Similar to whistling ducks living today, which have similar claws, they probably possessed the ability to perch on trees during periods of rest,” Mayr says.

Four species of waterfowl have been found at the Hammerschmiede site. Allgoviachen tortonica is the largest, weighing about two kilograms and reaching 70 centimeters in body length. The scientific name reflects the Allgäu region in which it was found, and the Tortonian epoch from which the find originated. “Its phylogenetic position is currently unresolved,” Mayr says, “Despite similarities to living shelducks and to the knob-billed duck, a number of primitive features suggest that Allgoviachen is not closely related to any of the waterfowl living today.”

Unlucky duck may have taken an unlucky dip

The present-day clay pit was traversed by rivers several million years ago. The complete Allgoviachen leg found by the researchers had been severed in the area of the thigh. This raises the possibility that it could have been left over from a meal made by one of the nearly meter-long snapping turtles that populated the Hammerschmiede river in great numbers. “It is consistent with the leg being bitten off while Allgoviachen was swimming. The complete preservation of all bones backs up that scenario,” explains excavation director Thomas Lechner.

Usually, skeletal elements belonging to an individual bird are transported by the river over distances of many meters. This was the case with the wing and coracoid bones of a very small duck species, Mioquerquedula. These bones were found over a distance of ten meters in the course of the excavation. Mioquerquedula is a true dwarf, smaller than the smallest dwarf waterfowl living today. Its body was about 25 centimeters long and it probably weighed only 300 grams. Present-day pygmy waterfowl such as the blue-billed teal (Spatula hottentota) and the African pygmy goose (Nettapus auritus) live exclusively in the tropical zones of Africa.

The morphology of the claws of the new waterfowl (Allgoviachen tortonica) resembles the claws of tree-dwelling waterfowl (Dendrocygna) more closely than those of water-dwelling ducks (Hymenolaimus).

“The latest finds once again underline the worldwide importance of the Hammerschmiede clay pit for the study of the animal world in the time between twelve and eleven million years ago,” says Professor Böhme. “So far, we have found more than 140 different vertebrate species at this site, including the first upright-walking ape, Danuvius guggenmosi,” Böhme adds. Under her direction, excavations at the Hammerschmiede have been taking place since 2011.

A giant crane from southern Germany

Gerald Mayr et al, Nearly complete leg of an unusual, shelduck-sized anseriform bird from the earliest late Miocene hominid locality Hammerschmiede (Germany), Historical Biology (2022). DOI: 10.1080/08912963.2022.2045285

Citation:

Researchers find eleven million-year-old fossils in southern Germany’s Hammerschmiede clay pit (2022, March 9)

retrieved 9 March 2022

from https://phys.org/news/2022-03-eleven-million-year-old-fossils-southern-germany.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

For all the latest Science News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.