500-million-year-old fossilized brains of Stanleycaris prompt a rethink of the evolution of insects and spiders

Royal Ontario Museum revealed new research based on a cache of fossils that contains the brain and nervous system of a half-billion-year-old marine predator from the Burgess Shale called Stanleycaris. Stanleycaris belonged to an ancient, extinct offshoot of the arthropod evolutionary tree called Radiodonta, distantly related to modern insects and spiders. These findings shed light on the evolution of the arthropod brain, vision, and head structure. The results were announced in the paper, “A three-eyed radiodont with fossilized neuroanatomy informs the origin of the arthropod head and segmentation,” published in the journal Current Biology.

It’s what’s inside Stanleycaris’ head that has the researchers most excited. In 84 of the fossils, the remains of the brain and nerves are still preserved after 506 million years.

“While fossilized brains from the Cambrian Period aren’t new, this discovery stands out for the astonishing quality of preservation and the large number of specimens,” said Joseph Moysiuk, lead author of the research and a University of Toronto (U of T) Ph.D. Candidate in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, based at the Royal Ontario Museum. “We can even make out fine details such as visual processing centers serving the large eyes and traces of nerves entering the appendages. The details are so clear it’s as if we were looking at an animal that died yesterday.”

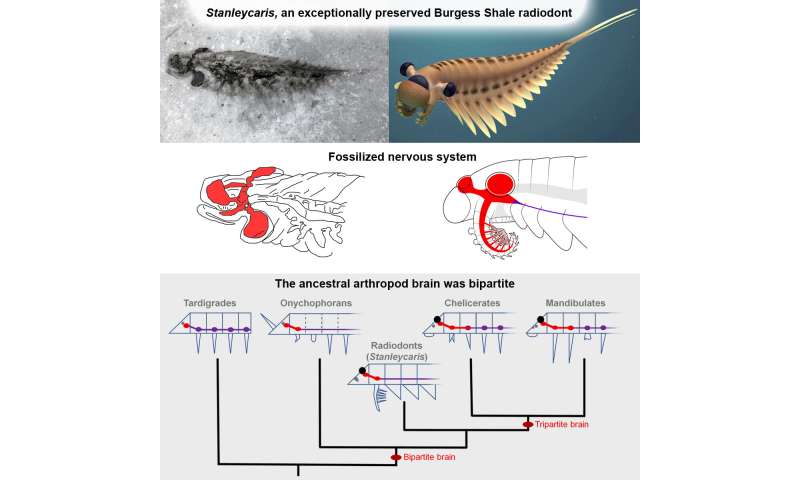

The new fossils show that the brain of Stanleycaris was composed of two segments, the protocerebrum and deutocerebrum, connected with the eyes and frontal claws, respectively. “We conclude that a two-segmented head and brain has deep roots in the arthropod lineage and that its evolution likely preceded the three-segmented brain that characterizes all living members of this diverse animal phylum,” added Moysiuk.

In present day arthropods like insects, the brain consists of protocerebrum, deutocerebrum, and tritocerebrum. While the difference of a segment may not sound game-changing, it in fact has radical scientific implications. Since repeated copies of many arthropod organs can be found in their segmented bodies, figuring out how segments line up between different species is key to understanding how these structures diversified across the group. “These fossils are like a Rosetta Stone, helping to link traits in radiodonts and other early fossil arthropods with their counterparts in surviving groups.”

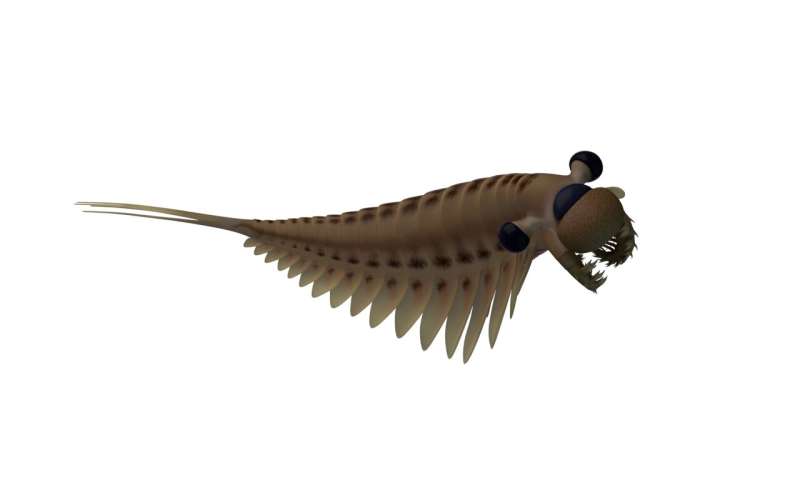

In addition to its pair of stalked eyes, Stanleycaris possessed a large central eye at the front of its head, a feature never before noticed in a radiodont. “The presence of a huge third eye in Stanleycaris was unexpected. It emphasizes that these animals were even more bizarre-looking than we thought, but also shows us that the earliest arthropods had already evolved a variety of complex visual systems like many of their modern kin,” said Dr. Jean-Bernard Caron, ROM’s Richard Ivey Curator of Invertebrate Paleontology, and Moysiuk’s Ph.D. supervisor. “Since most radiodonts are only known from scattered bits and pieces, this discovery is a crucial jump forward in understanding what they looked like and how they lived,” added Caron, who is also an Associate Professor at the U of T, in Ecology & Evolution and Earth Sciences.

In the Cambrian Period, radiodonts included some of the biggest animals around, with the famous “weird wonder” Anomalocaris reaching up to at least 1 meter in length. At no more than 20 cm long, Stanleycaris was small for its group, but at a time when most animals grew no bigger than a human finger, it would have been an impressive predator. Stanleycaris’ sophisticated sensory and nervous systems would have enabled it to efficiently pick out small prey in the gloom.

With large compound eyes, a formidable-looking circular mouth lined with teeth, frontal claws with an impressive array of spines, and a flexible, segmented body with a series of swimming flaps along its sides, Stanleycaris would have been the stuff of nightmares for any small bottom dweller unfortunate enough to cross its path.

-

Reconstruction of Stanleycaris hirpex. Credit: Art by Sabrina Cappelli © Royal Ontario Museum

-

![500-million-year-old fossilized brains of stanleycaris prompt a rethink of the evolution of insects and spiders]()

Fossil specimen of Stanleycaris hirpex. Dark material inside the head is the remains of nervous tissue, specimen ROMIP 65674.2. Credit: Jean-Bernard Caron © Royal Ontario Museum

About the Burgess Shale

For this research, Moysiuk and Caron studied a previously unpublished collection of 268 specimens of Stanleycaris. The fossils were primarily collected in the 1980s and 90s from rock layers above the famous Walcott Quarry site of the Burgess Shale in Yoho National Park, B.C., Canada, and are part of the extensive collection of Burgess Shale fossils housed at ROM.

-

Paper summary, showing the interpretation of the nervous system from fossils of Stanleycaris and implications for understanding the evolution of the arthropod brain. The brain is represented in red and the nerve cords in purple. Credit: Jean-Bernard Caron © Royal Ontario Museum

-

![500-million-year-old fossilized brains of stanleycaris prompt a rethink of the evolution of insects and spiders]()

Fossil specimen of Stanleycaris hirpex. Dark material inside the head is the remains of nervous tissue, specimen ROMIP 65674.1. Credit: Jean-Bernard Caron © Royal Ontario Museum

The Burgess Shale fossil sites are located within Yoho and Kootenay National Parks and are managed by Parks Canada. Parks Canada is proud to work with leading scientific researchers to expand knowledge and understanding of this key period of earth history and to share these sites with the world through award-winning guided hikes. The Burgess Shale was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980 due to its outstanding universal value and is now part of the larger Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks World Heritage Site.

Fossils of Stanleycaris can be seen by the public in the new Burgess Shale fossil display in the Willner Madge Gallery, Dawn of Life at ROM.

Massive new animal species discovered in half-billion-year-old Burgess Shale

Joseph Moysiuk, A three-eyed radiodont with fossilized neuroanatomy informs the origin of the arthropod head and segmentation, Current Biology (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2022.06.027. www.cell.com/current-biology/f … 0960-9822(22)00986-1

Provided by

Royal Ontario Museum

Citation:

500-million-year-old fossilized brains of Stanleycaris prompt a rethink of the evolution of insects and spiders (2022, July 8)

retrieved 8 July 2022

from https://phys.org/news/2022-07-million-year-old-fossilized-brains-stanleycaris-prompt.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

For all the latest Science News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.